. . .

. . .

Academic libraries build collections in the context of their parent institutions, primarily to support the institution’s research, teaching, and learning mission. They also build collections that document and preserve the cultural and scientific heritage of our society to represent a wide range of perspectives. Finally, the collections are intended to represent the students and their diverse needs and interests as learners, building and contributing to the school’s mission and vocation. This last point creates a sense of belonging, representation and access for students. In these efforts, university libraries are developing approaches that address calls for greater diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) with a focus on creating space for and the perspectives of historically marginalized groups.

This was a project I took over to help ensure this work was championed and steered effectively within the context of collection developement. It was preformed from Fall 2022-Summer 2023. The goal was to decenter normative white perspectives and focus diversity markers for historically marginalized groups who are a priority within the institution. The institution is predominately BIPOC, graduate students, many of whom study :Womanist Theology, Black Liberation Theology, Latinx Liberation Theology, LGBTQ and gender studies. As a consequence the collection already reflects a diverse body and coursework. We feel it pertinent to assess our internal biases and blind spots, to ensure our collection accurately carries out the institution’s DEI mission.

. . .

Through a multi-stage process, we gathered the relevant information and perspectives that informed our audit guide. The first step for was determining how “diversity” was to be defined in the context of these collections. This involved getting larger institutional stakeholders involved who guide the school’s value work. This is an important reminder that no library is ever “neutral”. There are tradeoffs and risks involved in how collections diversity is defined.

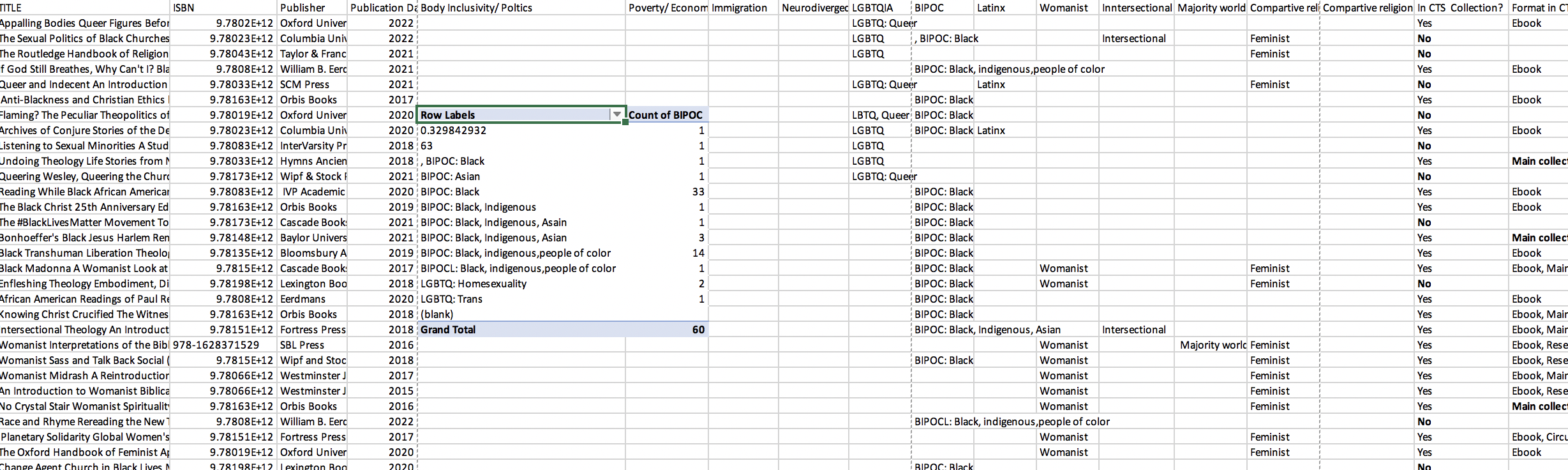

Our goals were discrete; increase the representation of works written by authors other than cis white males. Rather than approaching “diversity” in aggregate, we were highly specific in what we meant by using terms, such as: “BIPOC”, “majority world”, where specifically in Asia, of Africa, the book referenced. Our diversity markers also have room for intersexuality (social identities, such as: race, gender, sexuality, class, marital status, and age) and overlap in dynamic ways. This captures the complexity of the human experience and provides an expanded, more accurate, three-dimensional view of inclusion.

In our initial control we kept it to digital formats only (as the school is nearly fully remote and that is where our budget considerations are focused heavily) and from a selection of professionally endorsed publishers, within the most widely studied subject area (hermeneutics) for the school’s discipline (theology). Finally, I designed the data collection and tracking progress for our DEI audit to be sustainable with established metrics of progress,

This process allows us to see the overall composition of the current collection and for us to evaluate what is strong about our collection and areas that could use improvement. Computational data points can be looked at in a more granular level with pivot tables. Data tells a narrative and helps to illuminate needs for acquisition of material to other stakeholders. The gaps identified will help to determine not only what new materials are needed, but also what materials can be discarded or reframed. Furthermore, it provided us with a map to extend our audit outward to other formats, types, subject matter, and future methodological approaches. We have performed three methodologies thus far, as a means to account for those limitations in our analysis and reporting. Another hope we had for this DEI audit was to compare our data against peer institutions to see where we stand, as well as, to share our findings. The Consortia and professional associations (such as The American Theological Library Association- Atla ) we are a part of, will also have valuable insight and might benefit from this focused review.

. . .

. . .

A take away from this DEI audit is. while a library-wide collection assessment may seem necessary in enacting a DEI collections strategy, an all-encompassing approach involves a number of challenges. Most notably, there is no one definition for “diversity,” nor is there a methodology that can adequately account for the full breadth of diversity within collections. There are also limitations to the tools and the metadata used to assess, which are often lacking in granularity. This meant, at times, I preformed lot of manual audit shaping upfront for this specific institution and library; for future sustainability

DEI auditing remind us that new insights within a pre-existing collection can be just as powerful as adding to or subtracting from the collection. Reframing a collection to achieve DEI-related goals can be implemented by identifying opportunities to apply new descriptions to the materials and/or present the materials in new ways through different discovery and access mechanisms. DEI auditing can be an avenue to inform databases about incomplete, outdated or inaccurate metadata. Vendors too are sent a strong message when library spending becomes advocacy of DEI related materials. These approaches can open up opportunities to engage stakeholder groups around undiscovered, or suppressed stories, and connect collections to new research; breathing life into the instruction, library and community.