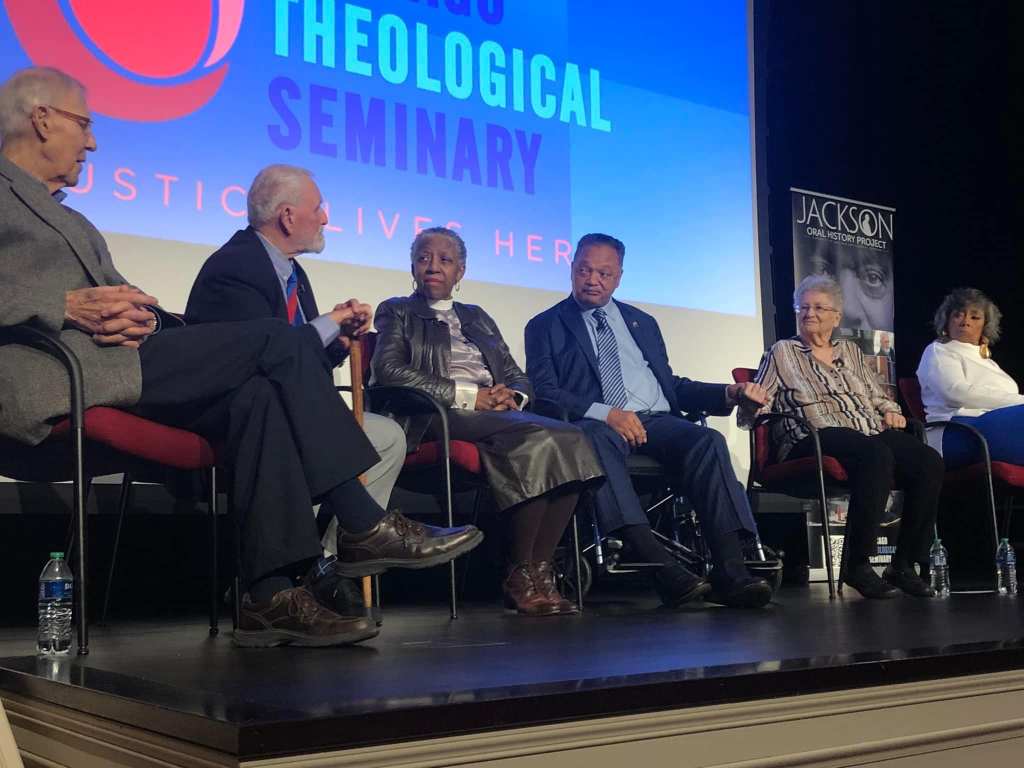

(L to R) Rev. Dr. Janette C. Wilson, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Betty Massoni, 02.08.2024

. . .

Jackson Oral History Project/ Operation Breadbasket Event 2024

Following Chicago’s long tradition of oral histories, the Chicago Theological Seminary has produced an oral history project on the city’s Civil Rights Movement — an archival work about Operation Breadbasket. The work will be featured in an exhibition at the Chicago History Museum in the spring, but a panel where the interviewees will be in conversation took place February 8th to a sold out audience .

This conversation is still as relevant and sadly, needed today as it was during the Civil Rights movement. Despite the powerful hold of weaponized American nostalgia and the progress narrative we tend to forget a crucial parts of our history: related to the Civil Rights Movement; notably the organized “massive resistance” by a white South united under the banner of white supremacy. It’s too easy to construct narratives that uphold status quo.

To counter such propaganda and hostility, civil rights activists and organizations embraced the philosophy and tactic of nonviolence and Christian ideals of forgiveness in the struggle for moral authority. By framing their protests in this way, the movement sought to win over the hearts and minds of white America. This is instructive for the contemporary struggles to remember that the Civil Rights Movement pushed back against the outright racism of Jim Crow, but also white mainstream media that questioned the legitimacy of nonviolent, direct action protests and civil disobedience.

Today’s protests are waging their version of this struggle to control the narrative of their movement. Looking back can enact a dialogue between past and present, drawing on recent experiences and past movements in shaping the terms and tactics of struggle. Much like Civil Rights activists of the 1960s challenged whites to see the hidden realities and injuries of racism; so too can organizers of movements such as Black Lives Matter and Free Palestine.

Thanks to a 17-year-old civilian’s smartphone recording, the world has witnessed the video of George Floyd’s strangulation by Derek Chauvin’s knee to the victim’s neck. The encounter made the historical abstraction of 400 years of racial oppression unbearably real to many people around the world.

Chauvin’s demeanor recalls James Baldwin’s description in his novel, “If Beale Street Could Talk,” of a racist police officer, the nemesis of the book’s black woman protagonist, who says she’s frightened to death by “the blankness of his eyes. If you look steadily into that unblinking blue, into that pinpoint at the center of the eye, you discover a bottomless cruelty, a viciousness cold and icy.” The inspiring actions of multiracial, multigenerational peaceful protesters are haunted by the nightmarish image of the indifference of Chauvin and others to Floyd’s pleading for his life.

Our perception of the effectiveness of protests cannot be separated from the anti-black violence that causes them. In this sense, the protest movement becomes more than simply a demand for change, for policies seeking reforms. The protest becomes an appeal to the conscience of indifferent, if not hostile, whites. From the civil rights movement’s demands for dignity and respect to current declarations that “Black Lives Matter,” “Palestine Liberation”, the goal is to forge empathy and solidarity persuade white people that we are all dehumanized by Colonialism.

One such model that was successful if we gaze back towards Civil Rights strategies were divest boycotts. Both the Civil Rights Movement, that focused on ending discrimination, especially segregation, and establishing equal rights in law, and the Black Power Movement that emphasized black pride and black community control were connected ideologically.

A Operation Breadbasket took on elements of Black power as that movement started to gain ascendancy. They were complementary, as one took an approach by negotiating with companies and practicing economic withdrawal – a looming background were riots happening across American cities in the 1960s.

. . .

Why Operation Breadbasket?

Operation Breadbasket was a part of the civil rights movement that often gets ignored, but in fact it was one of the most successful elements of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)’s activities.

One reason to talk about it is that it adds to our understanding of racial and cultural equity movements in the 20th century. Operation Breadbasket continued until 1971. Although Operation Breadbasket no longer exists in its current form, it continued as what is now known as Rainbow PUSH.

A second reason to talk about Operation Breadbasket is broader: it provides a good model for how consumer power can play an important role in social change. Operation Breadbasket provides a successful model of direct action that continues today. It is also a powerful illustration of how well-organized divestment boycott campaigns can work.

(L to R) Rev. Martin L. Deppe, Rev. David Wallace, Rev. Dr. Janette C. Wilson, Rev. Jesse Jackson, moderator Rev. Brian E. Smith (standing), Betty Massoni, Hermene Hartman, 02.08.2024

. . .

Boycotts and Civil Rights

Operation Breadbasket of course not first boycott movement used to fight anti-black racism in the US.

Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work

In 1929 Chicago, picketers launched a boycott of a department store called Woolworth under a “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign. Woolworth agreed to a policy of hiring 25% Black employees in its stores, resulting in 2,000 jobs.[7]

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

Perhaps the most famous example is the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a boycott beginning in December 1955 that went on for 381 days. The bus boycotts were about more than desegregating buses. Black Americans did not only want to ride buses alongside white Americans: they also wanted to drive buses and own bus companies.[

The Birmingham Campaign (1963)

Campaign to end discriminatory economic policies. It included a boycott of businesses that hired only white people or maintained segregated restrooms.

Selective Patronage

Reverend Leon Sullivan of Philadelphia selective patronage, which refers to the strategic withholding of black patronage from businesses that discriminate, especially on Black employment. Selective patronage was inspired by the sit-ins in the deep South.

Leon Sullivan created a program where teams of ministers negotiated for jobs with corporations doing business in Black communities, with the threat of boycotts. By 1963, this program had opened up 2,000 skilled jobs in Philadelphia. Sullivan was asked to present on this model to the SCLC in Atlanta. That presentation led to the creation of Operation Breadbasket in Atlanta in 1962.

. . .

Operation Breadbasket Historiography

Economic Liberation

Between 1916 and 1970, more than 6 million Black Americans relocated from the rural South to cities in Northern, Midwestern, and Western America. This Great Migration was prompted by the harsh segregationist laws and poor economic opportunities in the south. Economic opportunities for Black Americans during the first and second world wars helped to spur this trend.

When WWI ended many Black Americans were fired or expected to return to unskilled jobs. The Great Depression was particularly harsh on Black unemployment: in 1931, 58.5 percent of employable Black women and 43.5 percent of employable Black men were unemployed.

While Black employment rose during WWII and continued during the period of general economic prosperity in the 1950s, by 1960 the job ceiling for Black Americans became an increasing point of contention. By the mid-1960s the unemployment rate amongst Black Chicagoans was twice that of white Chicagoans, for example.

Deindustrialization and the loss of American manufacturing made this situation worse. At the same time, the mid-1960s was a period of protest – which in some cases resulted in violence. There was a growing sense that Black Americans “would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.

It was in this context that SCLC moved north in the 1960s to address a new form of segregation – the slum. Housing equality and economic liberation became focal points. Early housing efforts failed due to intransigence from the Mayor, and so jobs became the primary focus. Operation Breadbasket “was a response to the color line in employment.”

Operation Breadbasket

The SCLC first established Operation Breadbasket in 1962 in Atlanta. Breadbasket was explicitly modelled on Leon Sullivan’s selective patronage. Operation Breadbasket in Atlanta began with the bread industry. The first campaign was against Colonial Bakery, which gave in to Breadbasket’s demands after a boycott and picketing. Between 1962 and 1966, Atlanta Breadbasket won 4,000 jobs and $15 million of income to the Black community there.

Chicago Breadbasket

When SCLC moved north to Chicago, Operation Breadbasket was formed there and became a core element of the SCLC’s overall strategy. Specifically, Breadbasket was launched in Chicago in 1966 with a group of 60 pastors, many affliated with the Chicago Theological Seminary. Reverend Jesse Jackson led Chicago Breadbasket, with guidance from Martin Luther King Jr.. Breadbasket was significant in launching Jackson’s civil rights career.

(L to R) Rev. Martin L. Deppe, Rev. David Wallace, Rev. Dr. Janette C. Wilson, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Betty Massoni, Hermene Hartman, 02.08.2024

. . .

The Breadbasket Model

Operation Breadbasket had a number of components, but its main focus was creating job opportunities for Black Americans through consumer pressure. The model included six core steps, which is relevant and should be considered by divestment liberation movements today :

1. Information gathering: a team of clergy would go to the company and request a copy of its Equal Employment Opportunity Commission annual report, a document mandated by the 1964 Civil Rights Act. They also asked for salaries by category.

2. Committee Evaluation: Then, the committee would decide on a set of demands. The baseline was a minimum demand of 20% Black employees (28% of Chicagoans were Black at the time), but this could be adjusted based on factors like where the company was operating.

3. Education and negotiation: then a team of clergy would meet with company executives to try to reach agreement on targets and deadlines for a “covenant”, a written moral contract.

4. Economic withdrawal and picketing: when CEOs refused to share information or to continue discussions, pastors would call for a boycott from their pulpits. This would be coupled with picketing and leafleting.

5. Agreement/Covenant: when the Breadbasket team and the company agreed on a set of targets, they would formalize it in an agreement or covenant. At that time, any economic withdrawal would be officially called off. The agreements would be signed at a formal ceremony.

6. Monitoring: this was a later addition to the strategy, but it proved important. Breadbasket team members would regularly follow up to monitor the implementation of the agreements. When companies didn’t hold to their commitments (or reasonably close), Breadbasket would initiate another economic withdrawal.

. . .

Outcomes

Chicago Breadbasket began with the bread, milk, soft drink, and soup companies, before moving on to other industries like supermarkets and construction.

In the six years that Operation Breadbasket operated, it created 4,500 jobs for Black Chicagoans, an estimated $29 million in income annually. That’s not including the income it created for black products and service contracts – if you include that, Breadbasket created $57.5 million annually for the African American community by 1971 (equivalent to $391.8 million in 2016 dollars).

Operation Breadbasket is forerunner to Operation PUSH (1971), which is now the Rainbow PUSH Coalition (formed in 1987).

The Challenge

The preservation and creation of Civil Rights Archives like the Jesse Jackson Oral History Archives to reconnect former movements to the present, to preserve movement-related materials and make these primary sources available to researchers, activists and participants.

Civil Rights Movement Archive (CRMA)

LOC Civil Rights History Project

Stop Hate for Profit boycott movement, which is calling on companies to boycott Facebook Ads until Facebook agrees to establish and empower permanent civil rights infrastructure so products and policies can be evaluated for discrimination, racism, and hate by experts.

Stop Hate for Profit is promoted by a coalition of various racial equality groups, as well as at least one union and Mozilla.

Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) is a Palestinian-led movement for freedom, justice and equality. BDS upholds the simple principle that Palestinians are entitled to the same rights as the rest of humanity.

On behalf of those who worked to record and prepare these oral history interviews related to activism during the Civil Rights Movement, I am honored that the Chicago Theological Seminary has chosen to add these interviews to the Jesse Jackson Oral History Project/ Archives. Thank you to the Donnelley Foundation for their generous grant and support of this undertaking. Finally, thank you especially to the lifetime of work and struggle by Breadbasket and Civil Rights activists: Rev. Martin L. Deppe, Rev. David Wallace, Rev. Dr. Janette C. Wilson, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Betty Massoni, Hermene Hartman. Thank you for permitting us to preserve your oral testimonies and memories for the future.

Leave a comment